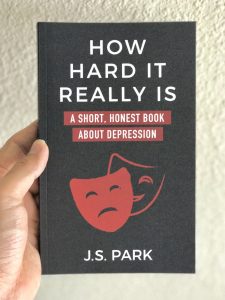

Depression. A fragile and, at times, controversial topic, it’s one largely ignored by the church as an institution. Many disbelieve its validity as a condition and most don’t know how to help someone suffering from it. That’s where J.S. Park hopes to shed some light with his book “How Hard It Really Is: A Short, Honest Book About Depression.”

Park, a pastor and hospital chaplain, spent a year and a half conducting research and interviews and surveying scores of individuals for his book in the hopes that it will help people who have depression and serve as a “primer” for those who don’t but who want to understand the issue and help those who do. “Depression is so misunderstood and mishandled that it comes with a built-in loneliness,” Park notes. “The book has a ton of different angles, from scientific to personal to psychological to theological because we’re all wired differently, and I’m hoping even one section can reach someone where they are.”

In the preface, Park writes, “Depression is a rumor, until it is a reality, and then it’s as if nothing else was ever real. Still, no one will believe you. I find it hard to believe it myself. I wrote this book for those who believe, and for those who want to.” Smartly, the book looks at depression from a myriad of angles. It details the science of depression from biological, social, and psychological viewpoints and seeks to discover whether depression is a disease or a choice. It examines the progression of therapy as a solution. It also discusses the age-old romanticism of depression—the idea that “the word ‘depression’ has been increasingly hijacked into a cult-like subculture of quirkiness”—and how technology has created an easier platform for this.

In part, the book details some of Park’s personal fight with depression; he knows what the struggle feels like. Because of this, the book doesn’t read like a clinical description written by an outsider. Instead the text illustrates what happens in the mind of someone with depression and gives depth to what it feels like and how someone can get through depression. It provides information gathered by surveys to present a well-rounded look at depression, and even records an interview with a depressed doctor.

In what I believe is one of the best sections of the book, Park discusses the “advice” people are often quick to distribute. This occurs in church and pop cultures alike. Both “endorse a sort of ‘powering through’ because it really translates to, ‘I don’t have time to get involved with your struggle.’ What’s really being said is: ‘Pray more and be positive so I don’t have to deal with you.’” This may be the most notable chapter for those who don’t have depression: for someone who’s trying to help a loved one, it could be a revelation; for Christians, it’s imperative to understand how to love someone in their depression.

When I asked Park how he handles this type of “advice,” he told me, “I’m learning that bad advice like ‘pray more’ or ‘be positive’ is more of a coping mechanism for those who don’t know what to say, or want to say something valuable rather than looking helpless, or are too scared to enter the dark with a person who has a mental illness. I think most Christians get caught up by this idea that they need to look like they have an answer for everything or their faith is at stake. The stronghold of ‘certainty’ is such a big deal in Christian-world, because there’s this dynamic with looking like a ‘good Christian’ when you know more stuff. Saying “I don’t know what to say” is like a death sentence to so many Christians, but really, I’d be relieved if more Christians just admitted “I don’t know how to do this” and were open to learning. For a person with depression, there’s this almost two-prong battle of handling the dark inside and then handling other peoples’ responses and perceptions. That gets really old, really fast. But as a Christian myself, I want to have grace for those who lack grace. Of course, there are some Christians who will never get it and never see depression as a legitimate condition, but for others, I’m slower to build a conversation. It’s hard to explain myself a thousand times over and over, but humility has to go both ways. I need to be humble about those who don’t seem to get it, just as I’m hoping they’re humble about not getting it.”

As an alternative to easy platitudes, the text offers suggestions and advice from people who have depression on how friends and loved ones can help. I believe this section in particular will be enlightening to those who desire to help. Park carefully notes that it’s a messy affair to enter into someone’s darkness, but “[T]he best thing we can offer each other is each other…”

But Park doesn’t leave God out of it. I asked him how he brings his depression to God. “My template is the Psalms. The Psalmists expressed every possible emotion to God, mostly with no clear order, with a messy, slobbery, almost embarrassing vulnerability…it’s just crazy and all over the place. That’s the journey of faith, though. Whether your brain is broken by mental illness or you’re perfectly of sound mind, encountering God is never a straightforward path.”

In the last chapter of the book, he tells the story of Elijah, the Old Testament prophet who was ready to take his own life until God sent angels to bring him food and rest. Park knows God remains with him during his depression as well. “…God is there, a current of the divine, walking me home through the desert, until I am finally home with Him. There is, too, a Body of Bread and Living Water that has come for me. There is, in Jesus, sustenance, the friend, the healer, the Greater Nabi, the authority over winds and mountains, a coursing fire, a gentle whisper, the God who became a man just like me, and loved me enough to stay on that cursed tree.”

J.S. Park is a pastor, hospital chaplain, blogger, author, former atheist, recovered porn addict, sixth degree black belt, and suicide survivor. His books, including “How Hard It Really Is: A Short, Honest Book About Depression,” are available on Amazon.com. You can follow his blog at JSPark3000.tumblr.com.